Enhancing education in large animal medicine was central to the OVC’s relocation to Guelph in 1922. The college’s curriculum in Toronto included some livestock medicine but was predominantly focused on horses. The years that followed the OVC’s move would see the mostly equine curriculum transform to address livestock medicine and public health.

When the OVC’s student veterinarians began classes in the Fall of 1922, their exposure to livestock medicine became much broader than what they had experienced when the college was in Toronto. Student veterinarians had access to a greater variety of livestock on Guelph’s campus as well as access to instruction from OAC faculty in addition to OVC faculty.

Large animal veterinary education has expanded and diversified over the last century to reflect the changing role of large animals in people’s lives as well as wider transformations in animal agriculture and public health. Preventative medicine and critical care, as well as ambulatory services, herd health and population medicine, among others, have become hallmarks of large animal medicine education at the OVC. In this way, OVC graduates can respond to the veterinary needs of individual animals and herds, and also play a critical role in the health of Canadians and the food system.

Equine Medicine at the OVC

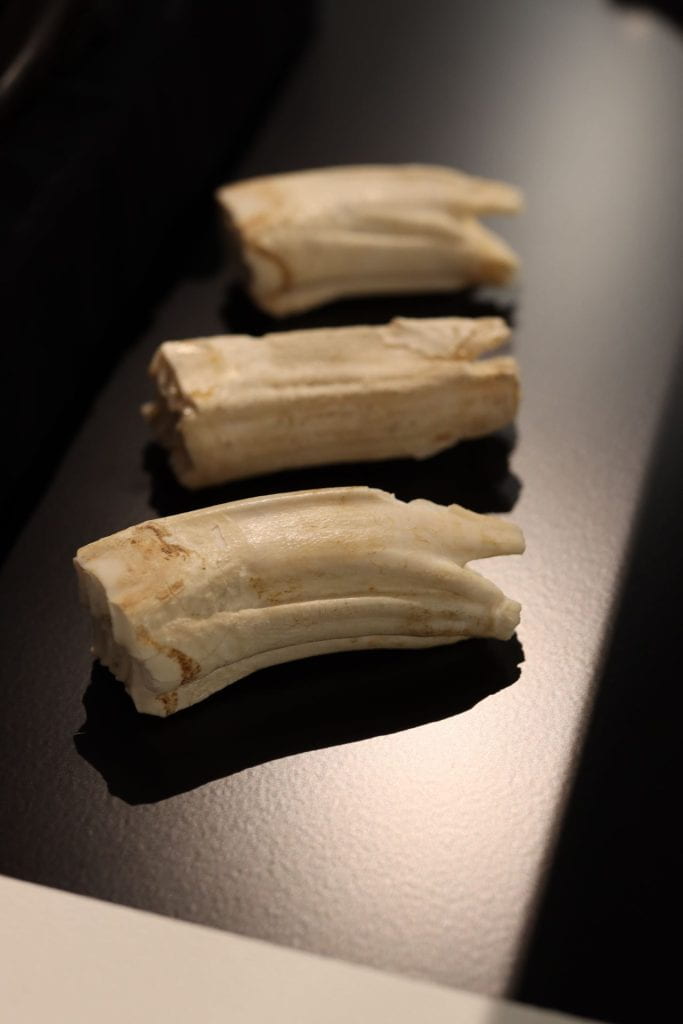

The need for well-trained equine veterinarians continued well after the OVC moved to Guelph in 1922. While large numbers of urban horses used for transportation services and other forms of work fell, horses continued to be used in smaller scale business operations such as milk delivery as well as in agriculture. Moreover, horses had long participated in recreation and sporting pursuits. The decline of working horses saw an increase of these sport and recreational horses and with that, a greater demand for veterinary care. The century after the OVC’s move to Guelph would see the college transform its equine medicine curriculum for graduates to greater address the veterinary needs of horses in these different roles. While preventative and critical care remain central to training in equine medicine, other areas of practice such as rehabilitation and sports medicine, as well as breeding, are offered to OVC’s student veterinarians.

Farm Service

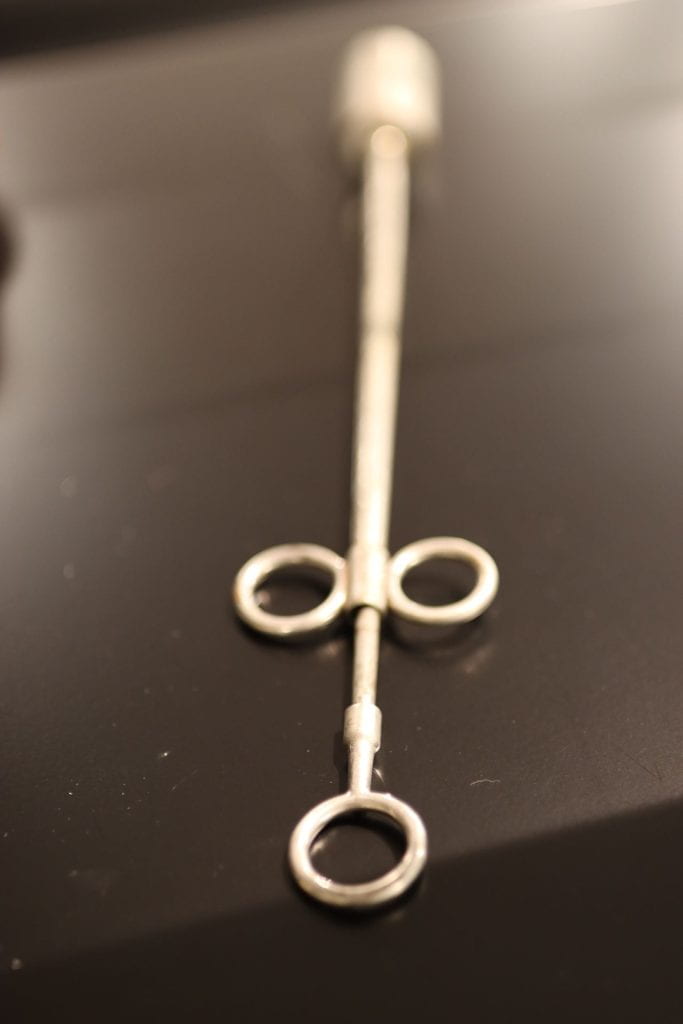

While the OVC teaching hospital provided student veterinarians with ample exposure to a variety of large animal clinical cases, by the early 1950s the American Veterinary Medical Association’s Council on Education recommended that the OVC establish an ambulatory service to provide on-farm veterinary instruction. In 1953, the Farm Service was established. Dr. Douglas Maplesden (OVC 1950) and Dr. Jack Cote (OVC 1951) began the program that saw small groups of students attending farm calls with clinicians. During these visits, students learned a host of skills such as evaluation, diagnoses, and therapy, client communication as well as the evaluation farm management practices. While many Farm Service calls dealt with routine livestock issues, student veterinarians were exposed to emergency situations such as injuries, difficult births, and illness. Preventative medicine programs were introduced later and included, among others, vaccination programs, deworming and other preventative procedures.

Veterinary Education and Wider Public and Ecosystem Health

From very early in its history, veterinary medicine has played a critical role in wider public health and environmental issues. The growth of Canada’s livestock industry, international trade and the emergence of a variety of infectious diseases throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries placed veterinarians in positions to influence policy and the ways in which people interacted with animals and the environments they shared. Training students for these opportunities has long been a part of the OVC’s curriculum which intensified after the college’s move to Guelph.

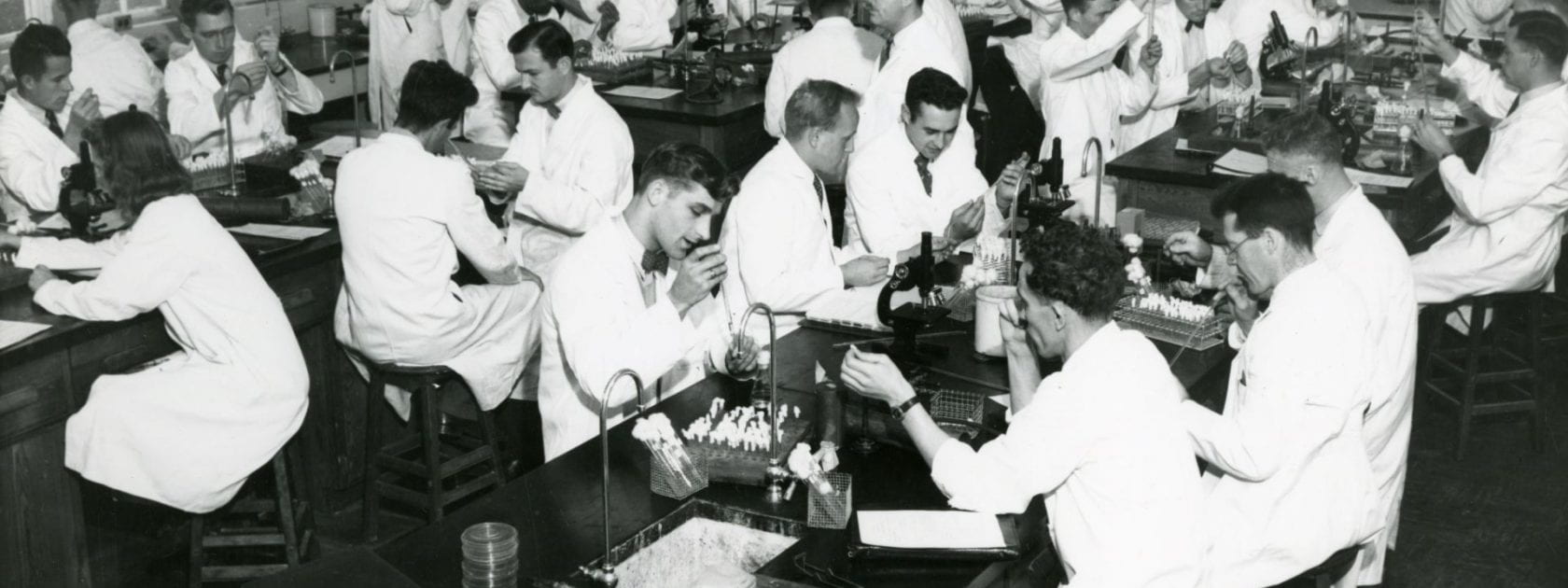

Beginning in the 1920s, in what might be described as the “post-equine” era (though equine medicine would continue to be a major focus for both teaching and research), student veterinarians increasingly saw more coursework in laboratory sciences such as pathology, bacteriology, among others, as well as coursework in meat and milk inspection. As the livestock industry continued to grow and transform throughout the 20th century, the OVC continued to innovate both its research and teaching offerings. In the 1980s, the Department of Population Medicine was created, providing students with the education necessary to provide important preventative care for producers who were often working with very narrow profit margins.

The 1990s and early 2000s saw further innovation in the offer of a final year rotation in Ecosystem Health. Veterinarians are often involved in larger issues outside of the clinic and hospital such as wildlife health and ecosystem monitoring and intervention, ecological disasters, and disease surveillance. This rotation has provided student veterinarians with field-based experiences with practitioners actively engaged in various areas of ecosystem health. These experiences are carried by students into their own practices or, for some, become an area of specialization and research.