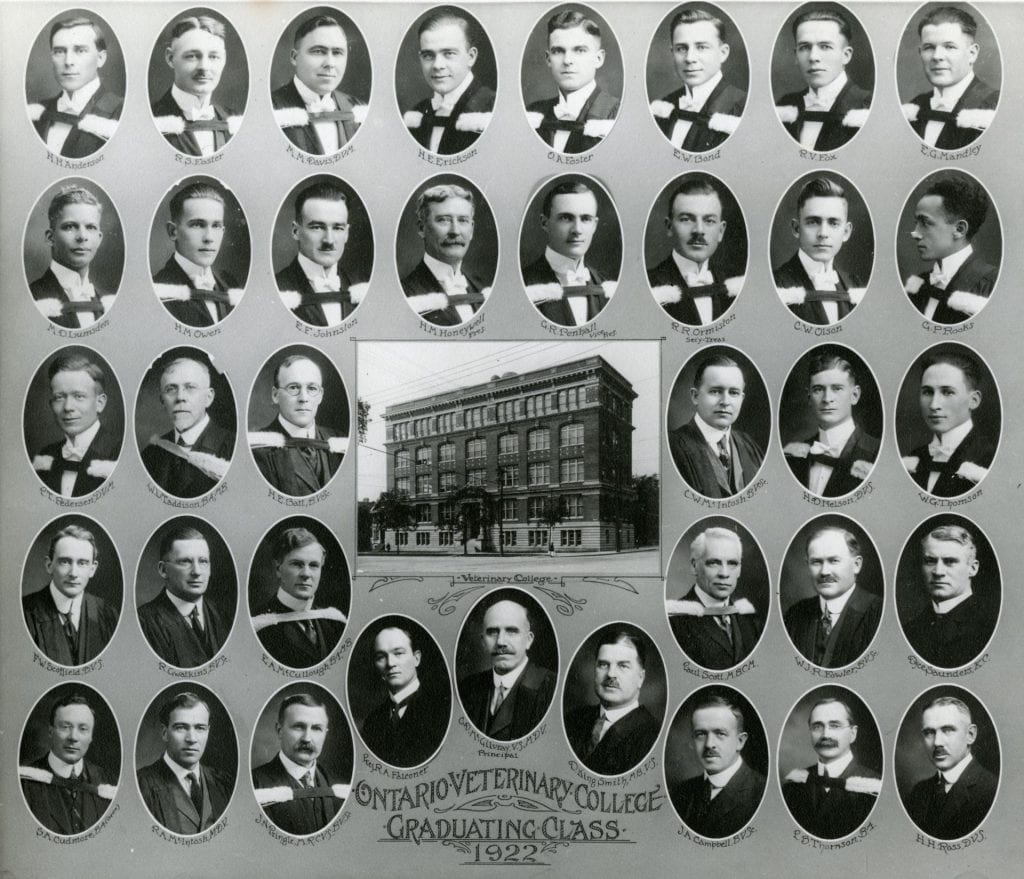

In 1922, the last class of student veterinarians graduated from the OVC in Toronto, closing a chapter of both the college and of veterinary education in the City. These eighteen graduates reflected the typical composition of the OVC’s student body observed for much of the college’s history. All men (the first woman, Dr. Elizabeth Barrie Carpenter, would not graduate from the OVC until 1928), most came from Ontario with a few from other Canadian provinces. Additionally, the OVC drew many students from the United States throughout its early history and, despite the existence of several American veterinary schools by the early 1920s, continued to attract many American students. Finally, two graduates in 1922 were from Trinidad and Tobago, continuing a tradition of student veterinarians attending the OVC from various parts of the Commonwealth.

Eighteen graduates in 1922 was a small class compared to the 120 the college typically produces today. Many veterinary colleges, including the OVC, struggled to attract students from the 1920s through to the early 1940s. Changes in admission requirements and lengthening the veterinary curriculum to four years, in part, explains the drop in enrollment. The OVC’s move from its original home in Toronto to the rural community of Guelph certainly could have affected students applying to the program. Additionally, changes in veterinary practice regulations, economic depression in the 1930s, as well as the outbreak of the Second World War affected admission numbers.

Commonwealth Students at the OVC

Two students from the Class of 1922, Matthew D. Lumsden and George P. Rooks, were from Trinidad. It was common throughout the 19th and early 20th century for schools like the OVC to admit students from throughout the Commonwealth. In particular, the Caribbean was a region that sent many students to the OVC beginning in the 1890s. For this region, the livestock industry was of particular economic importance and demanded trained veterinarians. We know very little about the experiences of BIPOC student veterinarians like Lumsden and Rooks, both well-educated men in Trinidad, at the OVC. Instances of racism are well-documented at other veterinary schools, but with no archive from these men and countless other students, their stories remain hidden. Even yearbooks like Torontonensis were highly-curated publications whose content was prepared by their student staff, not by the students themselves, and so it is not possible to even draw on them for an accurate snapshot of the student experience.

American Students at the OVC

A noticeable connection between certain members of the OVC Class of 1922 was their training at private American veterinary schools. There were many of these veterinary schools in the United States throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries and all had closed by the late 1920s. The OVC Class of 1922 mentions four – the Detroit Horseshoeing School, Chicago Veterinary School, McKillip Veterinary School, and the Kansas City Veterinary College. The closure of these four specific schools by 1920 left students with incomplete training which they then finished or began again at the OVC. Their motivation to travel to Canada and attend the OVC is largely unknown. Perhaps the OVC’s long history of educating American veterinarians offers a partial explanation. Regardless, this trend of student veterinarians travelling to the OVC from defunct, private American veterinary schools continued throughout the 1920s as they closed due to the changing regulatory environment within the veterinary profession. Moving forward from this period, the veterinary profession in both Canada and the United States would be defined by government and professional regulation in education, practice and service, largely cutting ties with the informally-trained past that characterized veterinary medicine throughout the nineteenth century.

Veterinary Families

OVC 1922 graduate William G. Thomson’s entry in Torontonensis states that “…desiring to follow in his father’s footsteps he came to the OVC in 1918.” The Thomson family are just one of dozens of “veterinary families” throughout the history of the OVC, with some families having three or four generations of OVC-trained veterinarians. The Barker Veterinary Museum is fortunate to have numerous examples of these families in its holdings.